Making housing, shaping old age

A summary of the PhD thesis of the same name, exploring industry engagement in older persons housing.

Download pdf

The experiences and meanings of old age are not fixed. They are not predetermined by biology (although some parts are) or by policy (again, some parts are). Of course, old age comprises many experiences and has many meanings. From different perspectives old age is an economic burden, an intergenerational imbalance, a long age of comfortable retirement, gendered poverty, precarity, isolation, or, for a range of aged care and service providers, increased demand and new commercial opportunities.

As a society we define the collective social

imaginaries of old age that underpin policy, products and practices. These are the images, stories and beliefs that mould assumptions about what old age

is, or what it should be. We make imaginaries of the third age - a time

of retirement, comfort, fulfilment – and of the fourth age – a time of

increased dependence and frailty. These social imaginaries

translate ambiguity and diversity into fixed, communicable, singular,

simplified, one-dimensional caricatures of the third age, and opposing images

of the fourth age, while ignoring uneven experiences and the transition between.

Before I started

researching housing and ageing, I was certain that old age, especially for

women, existed in a philosophical void. It was something that happened in

private, hidden and thinly theorised.

But old age is anything but personal.

Positive ageing is not an individual act, it does not exist independently of

the vectors of wealth, society, and housing.

Housing.

It is impossible

to consider old age without also talking about housing. Housing is central to

people’s physical and emotional wellbeing as they age. It also has a role in

social and economic policy. The Australian housing solution of mass homeownership

is embedded in culture and in policy that supports and subsidises this tenure. Homeownership

is the ‘fourth pillar’ of Australia’s retirement income insurance (joining the

age pension, mandatory and voluntary superannuation). Homeownership

is a solution to providing an affordable and secure old age because, by

retirement and with outright ownership assumed, housing costs are minimal and

households can live frugally on a state-provided pension that can be kept low relative

to other countries.

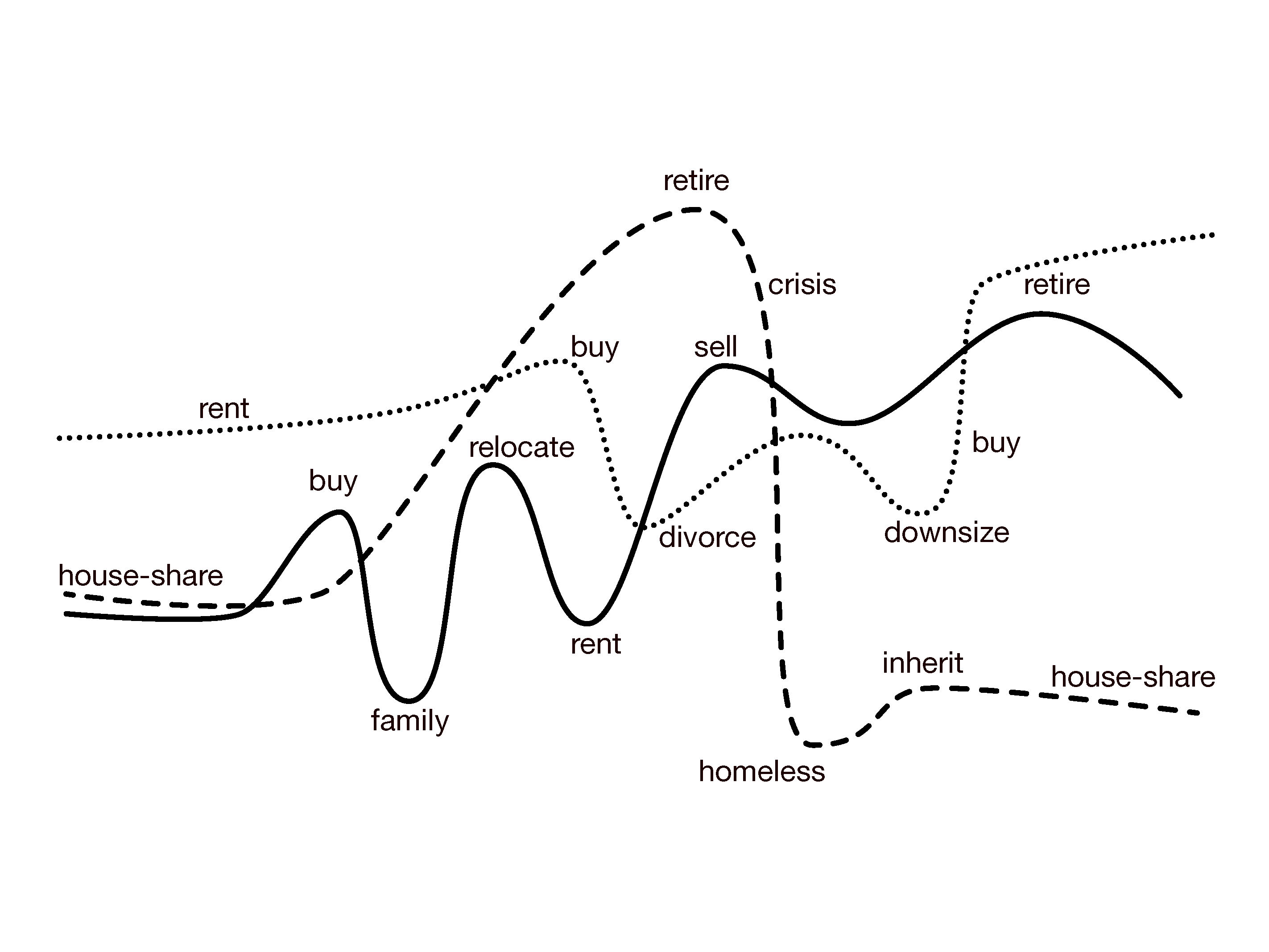

Yet, the homeownership pillar is wobbling. Increasing diversity and disparity in contemporary housing pathways, through the life course and for different generations, unsettle the foundations of this solution.

A crisis of housing affordability and changing (delaying, declining)

patterns of home ownership are likely to limit choices for younger generations (X,

Y and Z) as they reach retirement, as well as for current retirees whose

housing histories have not followed widely assumed norms. More are renting across all age groups, including low-income older

Australians, and disproportionately older women. Housing

and ageing are deeply entwined - in unsteady social structures, in concomitant quality of

life, and in the stories we tell about baby boomers and their

assumed housing wealth.

The ageing population (demand), and assumptions about wealthy baby boomers (capacity to fund demand) motivate the housing industry (along with other industries) to engage with the business of old age.

The retirement housing industry provides an example.

Retirement communities (both ‘villages’ and apartments) are a housing outcome that is, by definition, a market response to needs and choices of older people. This industry’s constituent companies operate within overlapping property and aged care interests. They are currently reconsidering what was historically a clear distinction between retirement housing (for the third age) and aged-care services (for the fourth age), motivated by growing demand as their residents age, and by a major transformation of aged care towards a market-led system.

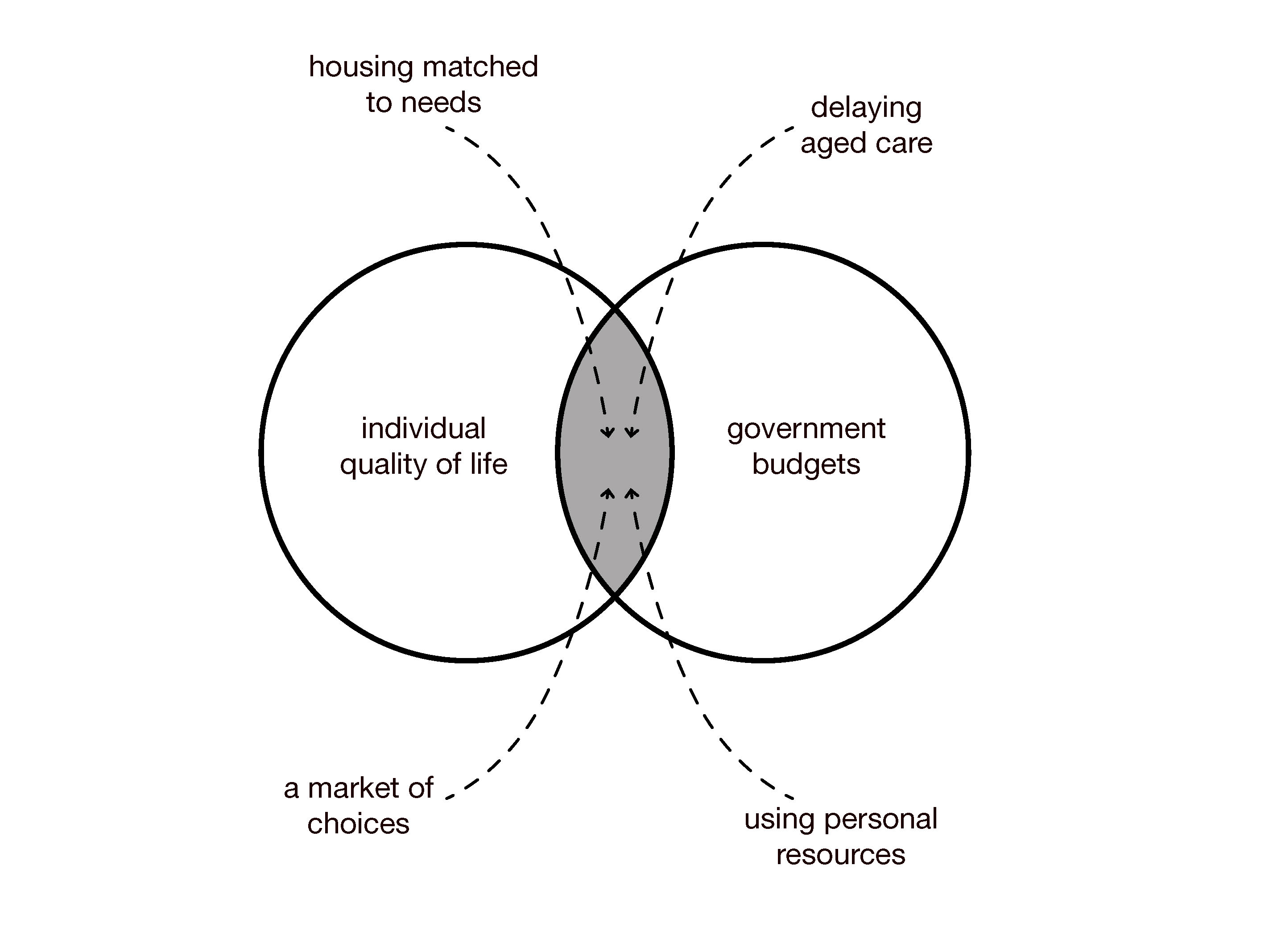

Industry representatives describe

retirement housing as a quality-of-life solution, offering appropriate housing

to support residents ageing in place, and a ready-made community to

counter social isolation. They describe it as part of the solution to reducing the

growing cost of the ageing population, providing relief for government budgets by

delaying entry to aged care, utilising the private sector and the personal

wealth of retirees, and building targeted local community infrastructure. And,

they describe it as a housing supply solution, setting out a path to downsizing

and more efficient use of existing housing stock in growing cities. Concerns

about old age and care are weaponised in the familiar and politicised housing solution

of more supply.

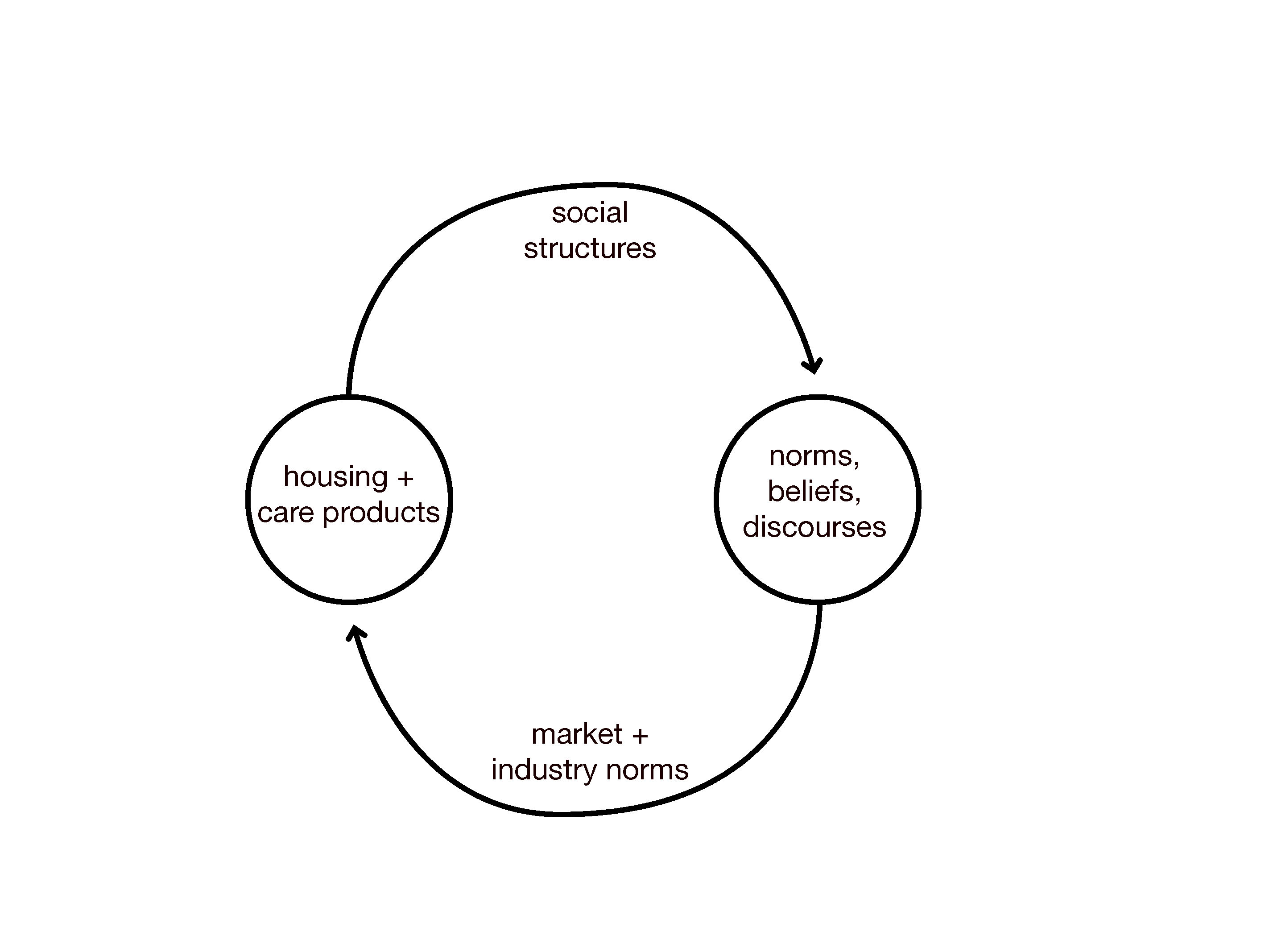

The process by which industry groups

reproduce and gradually transform social imaginaries of old age is

circular; ideas, discourses, beliefs and norms underpin social structures and shape the commercial housing-and-ageing

outcomes produced, which in turn reinforce those norms.

Three vignettes illustrate housing industry engagement in shaping beliefs about old age.

1. Shaping a ‘good’ old age

Industry actors reproduce the imaginary of the third age in marketing, in the way they talk about housing-and-ageing, and in the products they develop. They (along with the rest of us) collectively construct social imaginaries of what a ‘good’ old age is, layering personal perspectives, pre-existing beliefs, commercial interests, and dominant cultural ideologies including noisy narratives about the ageing population and baby boomers’ housing wealth.

In the third age imaginary of an independent, healthy,

social old age, retirees have the resources and agency to make individual choices

to meet their desires and needs. The industry’s political and consumer messaging

claims that by making good housing choices older Australians can enrich their

quality of life, use their housing wealth efficiently (for example by

downsizing or through reverse mortgages), and ultimately save government money by

reducing their later life healthcare costs. A ‘good’ old age for all.

Meanwhile, a cultural

obsession with autonomy and choice marginalises ‘other’ experiences of old age.

The focus on the third age can push the subsequent fourth age into the shadows.

This perspective treats dependence as a clinical and individualised need,

rather than as an essential aspect of relations between social beings

throughout life. It also defines the third and fourth ages as binary

conditions, when the reality is that the transition from independent to

dependent is diverse, uneven, susceptible to exogenous

events and luck, and mediated by social buffers (wealth).

Reinforcing a third age / fourth age binary, and a narrow imaginary of what a ‘good’ old age is, limits outcomes that can serve increasingly diverse older Australians. Third age aspirations will not adequately meet fourth age challenges.

2. Positioning housing (beyond design)

Urban and built outcomes reproduce and reinforce accepted views of third and fourth ages. Professionals involved in the production of housing, and especially in the development of retirement housing, embrace established positions (hopes) about housing and old age:

- That supportive housing delays the

need for aged care, prolonging the third age.

- That supportive housing enables

aged care (when it is needed) to be delivered through home-care services, limiting

the need for residential aged care.

- That housing-and-care outcomes can match changing housing-and-care needs, creating a gradual transition to increased care.

The belief that changing housing and care needs

can be matched efficiently by housing and care supply is the myth of a

seamless transition. This perspective is a myth

because it doesn’t acknowledge that supply of services (and housing) is locally

uneven, nor that there are many emotional, social, financial and cultural barriers

to changing housing through the life course.

Because the structural problems of

housing-and-ageing are knotted and complex, physical design solutions (accessible

homes, smart homes, universal design, retirement villages, and innovative

precincts that co-locate aged care with other multi-generational uses) are often seen (promoted) as panacea. Supply and design solutions provide a practical

course of action for policy makers, non-contentious and with few policy trade-offs,

and more tangible and immediate than addressing structural demand-side and supply-side

issues of housing affordability, taxation and welfare.

The benefits of designing for longevity through universal design are glaringly self-evident; this should be embedded in all apartment, house and urban design. But, design will never provide a solution to the social problems of housing-and-ageing.

3. Re-defining care

Aged care policy and philosophy – defining who provides care and how - has transformed during the past century, from a private family activity, to a professional nursing service often delivered in institutions, to a range of care services that can be purchased in a market.

The topic of aged care registered internationally in political agendas in the late 1970s, during the crisis of the welfare state that questioned the sustainability of state-supported systems. The ageing population ‘problem’ is a political, social, ideological and economic construction of resources and scarcity, rather than a purely demographic calculation. An ideology of individualism, personal responsibility, small government, and privatisation of services has supported major recent reforms that aimed to de-link care from accommodation and encourage ageing in place; to give older individuals more power in choosing their care; and to encourage private market involvement.

‘Care’ is a wide

spectrum of services. Some is regulated and funded as clinical aged care. Care

also includes services that simply make living more supported. Some of these

are government funded, via a needs assessment and waiting list, but they can

also be purchased privately in a growing care service market. The aged care industry actively redefines care as an individual

service and product. Morphologies such as retirement housing can be

infrastructures of positive ageing that support access to this wider,

limitless, definition of care, for older Australians who can afford it. As

providers pursue services that are profitable and that attract wealthy

retirees, choices and support will widen for some.

There are risks and potentials of redefining care in this way, and they follow the creases of uneven housing wealth.

* * *

Longer and more diverse lives mean there is cause for optimism. However, there are tensions between a global ageing population ‘problem’ and the individualised uncertainties of growing old. The risks of the enmeshed housing-and-ageing system are that property market conditions challenge the equity and resilience of the intergenerational social compact and undermine the wellbeing of older people. Housing wealth underpins unequal experiences of old age, yet the housing behaviours of older individuals are not to blame, and nor will they correct these imbalances.

The idea that ageing is a personal and individualised experience is damaging. Old age is shaped by material and social conditions; it is anything but purely personal. To make progress in supporting an ageing Australia, practical philosophies of old age can better centre housing systems and outcomes, and reconceptualise them as essential infrastructures of care beyond design and market responses.

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis