The story of retirement housing in Victoria

Building on research published in Urban Policy and Research (Volume 36, 2018) and research presented in the PhD thesis Making housing, shaping old age (2021).

Download pdf

Major social changes have shaped retirement housing as it exists today in Australia. These changes include the rise of the ageing population as an economic and policy concern, transformation of welfare and labour policies, and expansion – in time and diversity of meaning – of the ‘third age’ and retirement. Industry groups have been key participants in developing the aged-person housing model within the context of these major social and economic changes. Yet, despite major historical changes, the range of older persons’ housing being produced has not changed significantly in recent decades. With limited innovation of the housing model, some providers see an opportunity to increase support services instead, targeting the predicted desires and wealth of the baby boomer cohort. At the end of the 2010s, this is an industry waiting for disruption.

First, a brief history of retirement housing, through four phases:

1. Emergence (1860-1950)

In 19th-century Australia, housing and financial support for older people was provided by family, or by mutual or friendly societies. Friendly societies pursued benevolence over charity, allocating funds to those members judged to be deserving. Mutual societies and community groups developed and leased housing to older Australians of modest means as part of their wider social mission. Growth was slow until after World War I. However, it was significant in the longer term because it established not-for-profit organisations as retirement housing providers able to leverage reputation and land holdings in subsequent historical phases.

2. Expansion (1950-1975)

The federal government reshaped retirement housing after World War II by funding increased provision as part of a suite of post-war social policy measures. The Aged Persons Homes Act 1954 (Cth) provided capital to not-for-profits for housing that enabled ‘independent living’ for pensioners of modest means, to be constructed on land provided by local government and community groups, often supplemented by resident contributions. Through this program, not-for-profit groups constructed independent living units (ILUs) between 1954 and 1986, mostly small clusters of one-bedroom units.

However, subsidies were

increasingly used to fund residential aged care. Like many liberal

industrialised nations, by 1975 Australia had a highly institutionalised and

subsidised aged-care system. In response to the growing cost of aged care,

Australia joined much of the world in de-institutionalising aged care in the late

1970s and expanding the use of home care services. The federal government wound

back universal welfare and direct involvement in older persons’ housing.

3. Growth of a cottage industry (1975-2000)

Debt-free home ownership at retirement (the ‘fourth pillar’ of retirement insurance) and appreciating house prices introduced the option for many retirees to ‘downsize’ within the market, releasing funds for lifestyle and care costs. Not-for-profits first developed the resident-funded model in the 1970s, responding to localised demand, to reducing and ceasing government subsidies, and to growing financial capacity of home-owning retirees. The long-term lease tenure model encouraged retirees to move by reducing the initial cost of entry and by offering benefits of secure community living. The residents purchased a leasehold with a lump sum that was below market rate, paid ongoing maintenance costs, and shared in the costs of refurbishment, resale and capital gains of the housing at the end of their tenure. The intricacies of the model evolved incrementally in an ad-hoc way during the 1980s through various contractual arrangements.

The resident-funded model became an attractive proposition

for businesses entering the industry in the early 1980s. These included not-for-profit

and for-profit aged-care providers who added resident-funded retirement housing

to their offer, both to address community need for small single-person units

and to connect a stream of future customers to their core aged care service.

House builders and family businesses also entered the industry – for example

early industry pioneers Ian Ball and Zig Inge, who were small-scale suburban

house builders prior to becoming retirement housing developers and operators. Through

the 1980s and 1990s, private-sector providers differentiated their product from

the modest ILUs that had come before them by increasing dwelling size and

amenity to appeal to more affluent retirees. Retirement villages had already

matured in the United States (Sun City opened in Arizona in 1960) and

Australian providers sought to imitate the success of the ‘55-plus aspirational

play’, inaccurately assuming the local industry would echo the market in the

United States.

4. Entry of investment capital (2000-present)

In the 2000s, listed for-profit property development and aged-care service companies began to acquire existing retirement villages and to develop new villages. Much of the change and growth in the retirement housing industry since 2000 has been a result of these activities, characteristic of listed companies pursuing shareholder return. Large property development and investment companies entered the industry and grew their market by acquiring packages of both private and not-for-profit existing villages (and their contracts and residents). Retirement housing was attractive to property and investment companies for reasons beyond the straightforward aim of business operating profit.

They sought exposure to the growing baby boomer market,

viewed it as a ‘property play’ to accumulate well-located assets on their

balance sheets and as tax-effective investments that could offset obligations

in other diversified interests. Demand for their product is supported by the projected

number of older Australians, and by rising property values (strengthening

capacity to pay). Increased housing wealth means many operators have focused on

well-off retirees (and high-value established suburbs) and have retreated from

the industry’s early role in providing housing for older people of modest

means.

* * *

A quick overview of the retirement housing model:

The profit for retirement community operators derives from the initial sale and

subsequent rotation, or ‘churn’, of residents entering and exiting. A unique

element of the resident-funded model is the deferred payment arrangement, known

as the Deferred Management Fee (DMF). This sum is generally a percentage

reflecting duration of residence, calculated upon exit from the retirement

community and deducted from the unit sale price after the resident’s tenure. Residents therefore

pay a lump sum at entry, a weekly or monthly maintenance fee, and a sum when

they leave. The terms are managed by a

range of historically complex and often unique contracts.

Central to the system is a ‘downsizing differential’ that encourages retirees to change their housing - generated through a cost differential (unlocking

cash from the sale of the family home), and through support and amenity

(attracting the resident through either ‘push’ or ‘pull’ factors of need or

lifestyle).

* * *

Three stories about organisational change:

1. Growth since the 1980s has overwhelmingly been in the private sector, with limited new contributions from the not-for-profit sector.

Government policy catalysed the post-war provision of ILUs. When subsidies from the Aged Persons Homes Act ceased in 1974, the continued construction of housing for older people of modest means became unviable for not-for-profits. Instead, many have become more business-like in their approach and have intentionally broadened their offer from serving older people with modest resources to also participating in the ‘premium’ market.

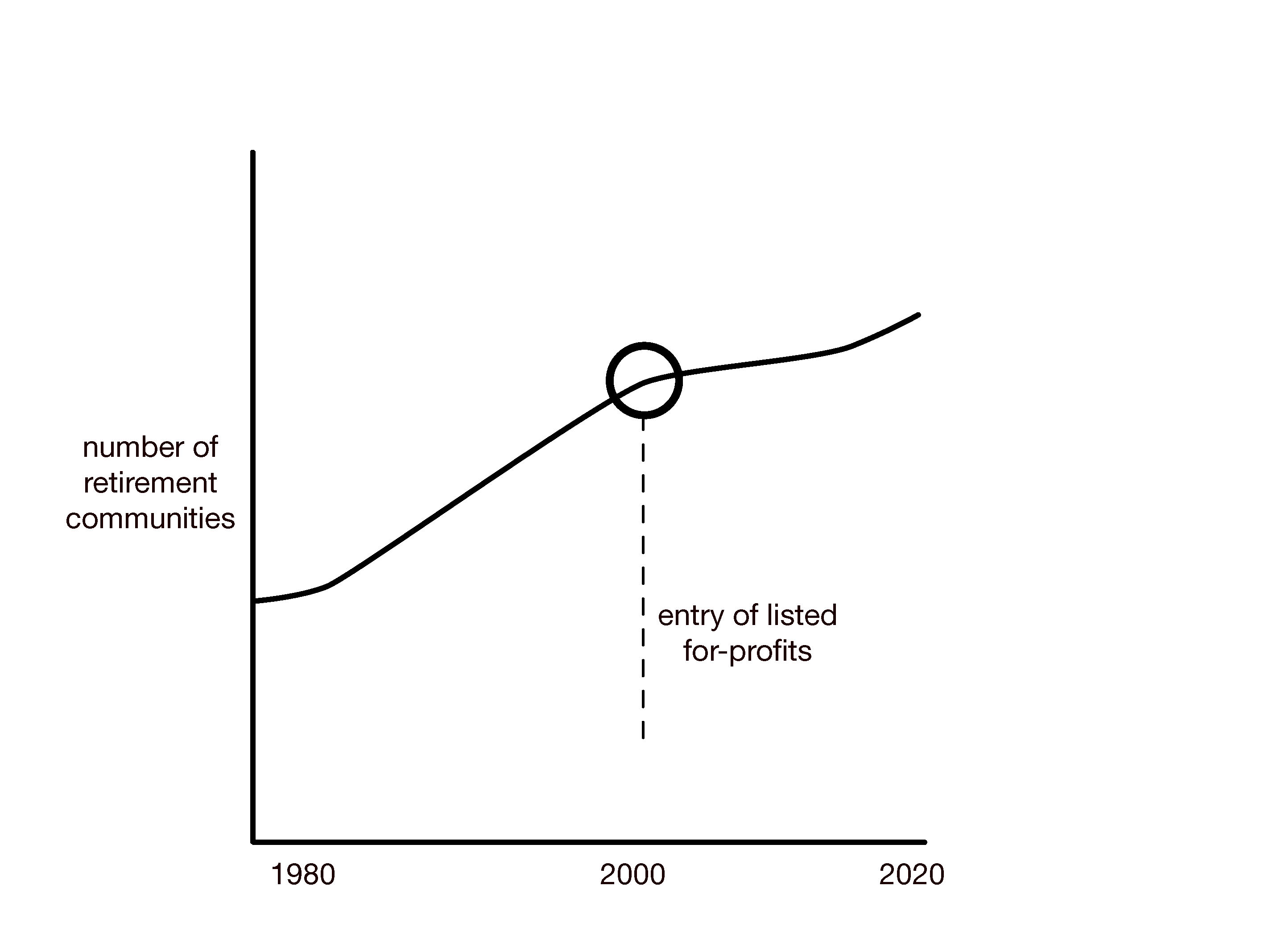

2. Village growth slowed and transformed in the early 2000s with the entry of listed for-profit companies.

The listed companies ‘cannibalised’ some of the villages developed by small-business providers, acting quickly and speculatively through acquisitions. Then, risk-averse and new to the operation of villages, they took time to assess the model’s performance, its return on investment and alignment with their consumer brands. The longer development times required to meet bigger yield expectations of large property developers also slowed new supply, and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis further limited new construction. The acquisitions of the 2000s were not an end to their buying and selling – retirement villages continue to be sold, bought, consolidated in investment moves.

3. Private and listed for-profit companies have grown a market of manufactured housing estates (MHEs).

MHEs are an evolution of the caravan park targeting the over-55s market. MHEs are not a new model, but new investors and operators have acquired, redeveloped and marketed these specifically for older people. Listed companies have grown the MHE subsector in Australia aggressively since the early 2000s. Companies identified an investment opportunity to accumulate land assets and lease them to a growing market of downsizing, home-owning households with a low net wealth. The tenure model (operators lease small lots of land for individually-owned relocatable homes) and cheap regional or urban-fringe land costs mean that capital and risks are lower and timeframes shorter than for standard village development.

Retirement housing companies and subsectors have continually

redefined their offer. They establish their identity to align with a

particular type of consumer and to differentiate themselves in relation to

other providers. Industry representatives talk of their organisation’s identity

as being ‘in their DNA’ –

fundamental to how they operate and deliver their products and services. This identity is not static but is constantly being reproduced and reshaped.

* * *

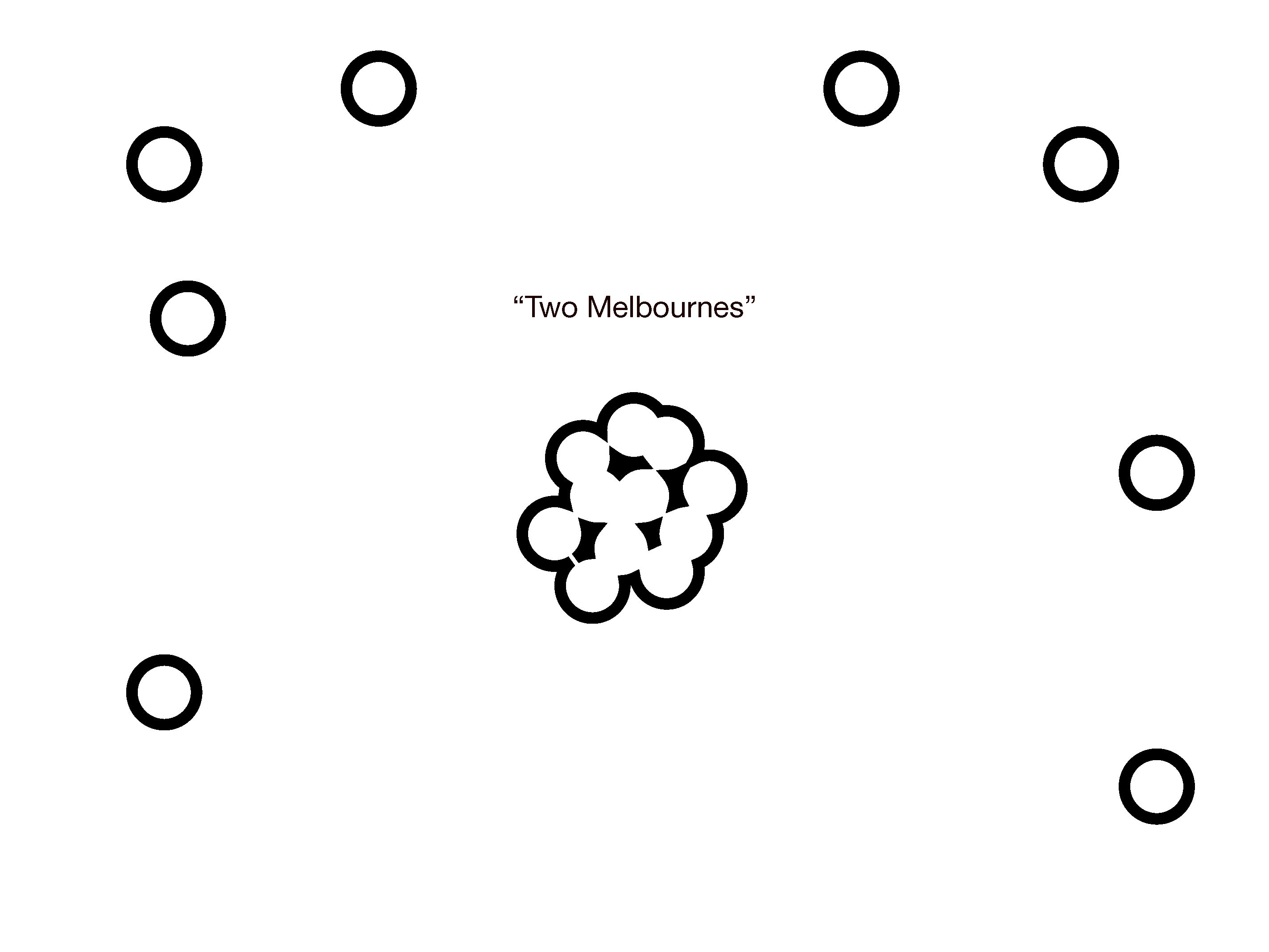

Built

outcomes of retirement housing have transformed from clusters of small ILUs in

the 1960s, to suburban villages with larger units and facilities in the 1980s

and 1990s, and more recently new high-density retirement apartments and MHEs. Luxury

retirement apartments and affordable manufactured housing are not innovations

from the broadacre outcomes of the 1980s, but are variants of ‘business as

usual’ industry practices. Their development is geographically segmented

between the well-serviced inner ring of the capital city Melbourne and a poorly

serviced suburban and peri-urban fringe. This urban segmentation challenges the ability to ‘age in place’ in

some localities and locks choices and needs of old age to property market

problems and solutions.

Retirement communities can be horizontal (‘broad-acre’) or vertical (apartments). Communities range from clusters of 6 homes to over 200 units. With greater scale comes expectation and capacity for expanded communal amenities. Supply of land and local household wealth makes development of certain housing outcomes more or less attractive in different localities.

Retirement communities can be horizontal (‘broad-acre’) or vertical (apartments). Communities range from clusters of 6 homes to over 200 units. With greater scale comes expectation and capacity for expanded communal amenities. Supply of land and local household wealth makes development of certain housing outcomes more or less attractive in different localities.

Three stories about changing spatial arrangement and built form:

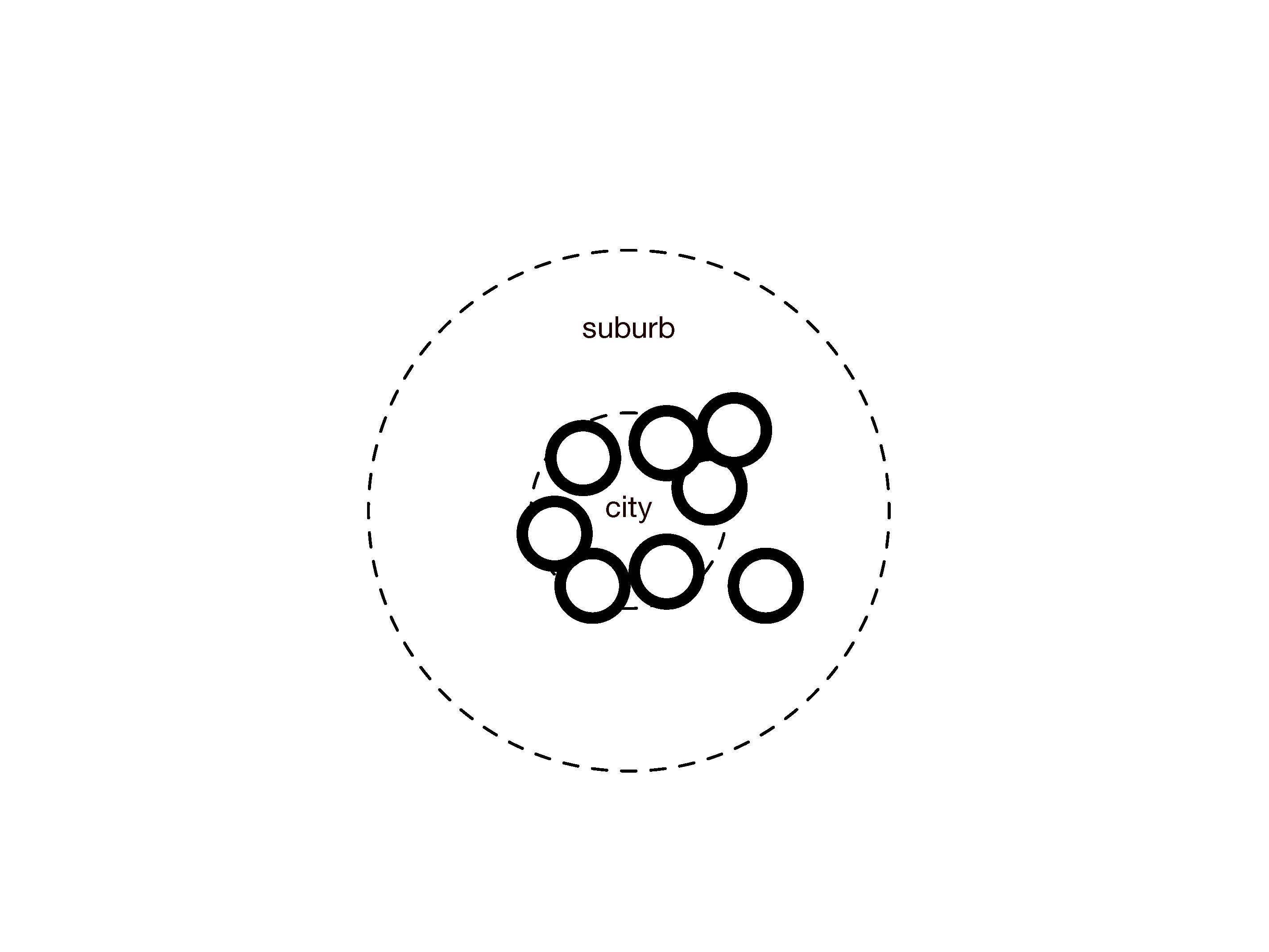

1. Suburban villages: ubiquitous to marginal

As Melbourne grew in the post-war period, small-scale housebuilders built suburban housing in new greenfield developments. Retirement housing developed in the 1980s and 1990s followed this suburban house-building practice. Retirement villages comprising single-storey detached or semi-detached units in affordable, suburban-fringe locations suited the construction practices of small-scale operators. Providers built villages ‘just a little bit further out’, beyond the edge of recently established suburbs. The price differential between the family home and the new unit was large enough to entice retirees to downsize.

Communal amenities in retirement villages provide a further incentive

to downsize. A pool, gym, spa, community lounge and garden

are the ‘bare minimum’ expected as part of the value of downsizing to a

retirement village rather than within the standard housing market. The

residents’ in-going contribution and regular maintenance fee pays for the construction

and maintenance of amenities. A large (fringe-suburban) plot of land is

necessary to spatially accommodate amenities in villages, and to achieve the required

number of residents to fund them.

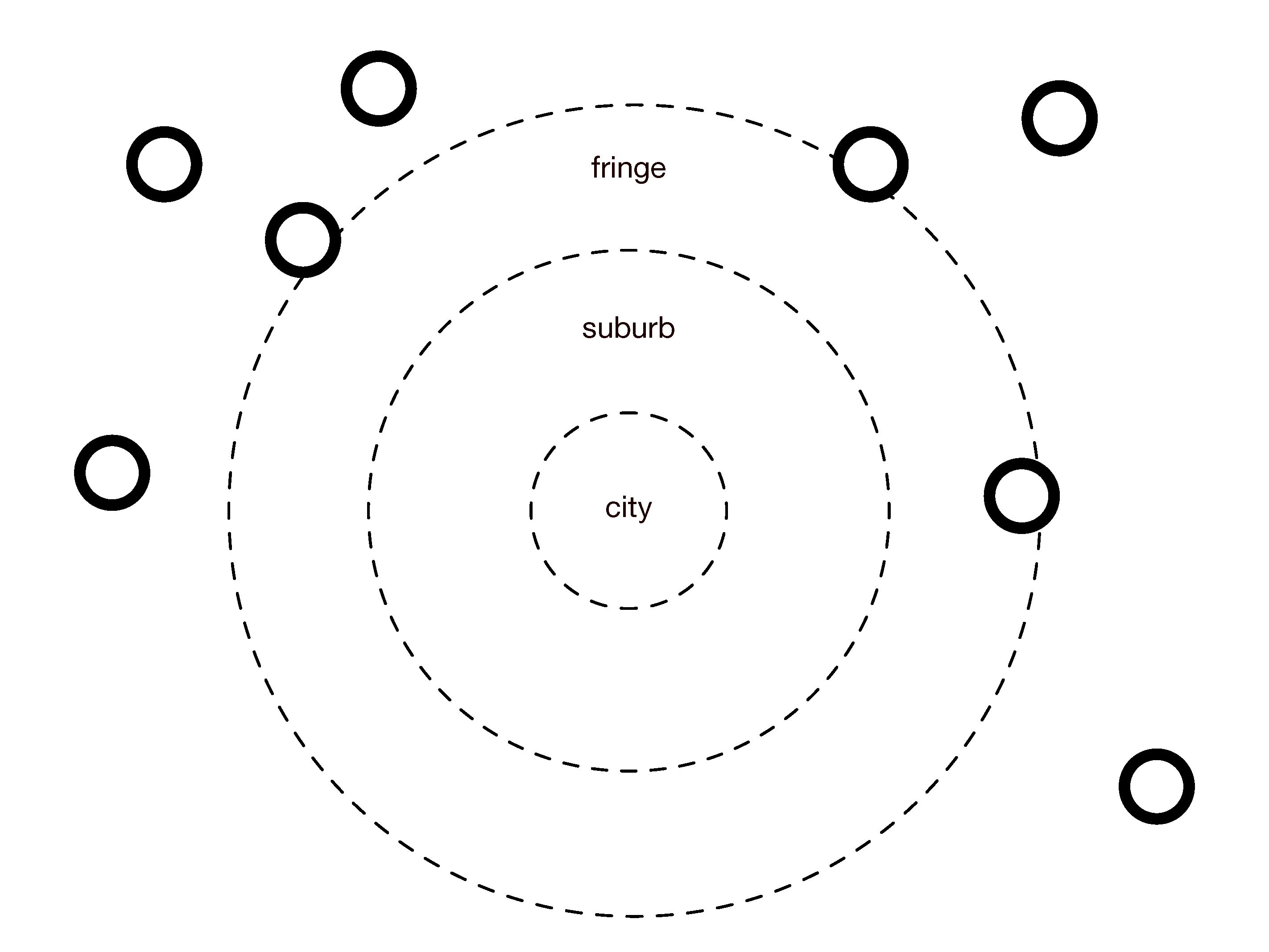

Urban densification and changing consumer expectations of housing and retirement challenge the suburban greenfield retirement-village solution. Housing density increased in the suburban-housing market, the supply of greenfield land became constrained, and retirees’ expectations of floor area increased, along with their capacity to pay for it. Consequently, it has become more difficult for retirement housing providers to compete with volume housebuilders for affordable land in outer-suburban areas. Slimmer margins for retirement housing providers in the suburban fringe opens up these localities to competition from manufactured housing and makes retirement apartments in urban-infill locations a relatively more attractive proposition.

Urban densification and changing consumer expectations of housing and retirement challenge the suburban greenfield retirement-village solution. Housing density increased in the suburban-housing market, the supply of greenfield land became constrained, and retirees’ expectations of floor area increased, along with their capacity to pay for it. Consequently, it has become more difficult for retirement housing providers to compete with volume housebuilders for affordable land in outer-suburban areas. Slimmer margins for retirement housing providers in the suburban fringe opens up these localities to competition from manufactured housing and makes retirement apartments in urban-infill locations a relatively more attractive proposition.

2. Retirement apartments: Developing density and selling service

The development of higher-density retirement apartments in the past decade reflects the aspirations of larger organisations (supply) and the capacity of retirees with housing assets in central well-serviced suburbs (demand). Two types of retirement housing providers have become involved in developing retirement apartments: established not-for-profits and listed, property-focused companies. The property-focused companies that entered the sector in the early 2000s seek land assets with dense development potential and they have the construction and funding capability for large projects. Established not-for-profits and care-focused providers develop retirement apartments that densify, and gentrify, the assets that they established as ILUs in the 1950s, or where they are co-located with aged-care facilities.

Retirement apartments feature a similar downsizing differential

evident in the suburban villages model, transposed to the inner suburbs and

reflecting higher prices and expectations of housing, lifestyle and service in

retirement. Inner Melbourne’s housing prices increased tenfold in 25 years between

1993 and 2018, providing a cohort of home-owning retirees with significant

housing wealth and the capacity to make choices about their accommodation. Higher-density

living is increasingly accepted across all age groups as an alternative to the

Australian legacy of suburban living, rather than as a transient housing choice

reserved for younger people. Downsizing has never been simply about releasing

housing wealth for retirement; it has also been an idea that retirees are

redefining their daily lives to be easier while remaining connected to the

social and cultural amenities central to their lifestyle.

Providers foresee the continued trajectory of greater service and amenity as part of the enticement to downsize, saying “it will be like living in a 5-star hotel.”

As universal and accessible design features gradually become standard in apartment design and customer expectations, the physical difference between apartments provided in the market and those operated as retirement living narrows.

Apartment developers will increasingly market and design in ways that attract the cohort of baby boomers. There are few barriers to developing and marketing apartments to downsizers within the broader housing market, outside of the special arrangements of the Retirement Villages Act. These would form a high-density urban variant of the ‘naturally occurring retirement communities’ (NORCs) that are common in the United States. Industry actors from outside of the retirement sector are also able to provide other retirement apartment differentiators, such as bespoke tenure (including through build-to-rent models) and access to care through a rapidly growing private personal services and care market.

Providers foresee the continued trajectory of greater service and amenity as part of the enticement to downsize, saying “it will be like living in a 5-star hotel.”

As universal and accessible design features gradually become standard in apartment design and customer expectations, the physical difference between apartments provided in the market and those operated as retirement living narrows.

Apartment developers will increasingly market and design in ways that attract the cohort of baby boomers. There are few barriers to developing and marketing apartments to downsizers within the broader housing market, outside of the special arrangements of the Retirement Villages Act. These would form a high-density urban variant of the ‘naturally occurring retirement communities’ (NORCs) that are common in the United States. Industry actors from outside of the retirement sector are also able to provide other retirement apartment differentiators, such as bespoke tenure (including through build-to-rent models) and access to care through a rapidly growing private personal services and care market.

3. Manufactured Home Estates (MHEs): Affordable housing for shareholder return

MHEs are more affordable than standard retirement villages because the providers have developed a unique model with three key features: an outer-suburban and regional land market (cheap land), cheap dwelling construction and a tenure arrangement whereby the resident owns the unit but leases the land it sits on, thus establishing eligibility for government income support payments which support the model’s viability.

Features of affordability have developed from the model’s caravan park legacy. MHEs are generally clusters of 30–60 homes with a community club house, located on suburban fringe and regional sites that are often poorly connected to public transport and community services. Modular housing is produced in factories and assembled above ground rather than on a slab foundation. The tenure model also follows the legacy of caravan parks; the resident purchases their movable home and rents the land by paying a site fee. Purchase of the unit requires payment of a lump sum, usually realised through the sale of a home, as banks do not offer mortgages for this depreciating asset. In-going residents are predominantly homeowners from suburbs where house price increases have been modest.

The three necessary features of the MHE model – its tenure, house design and geography – all present challenges to ageing in place. The

land rental model does not provide security of tenure, allowing the operator to

change conditions of lease according to the (landlord-privileging) regulations

of the Residential Tenancies Act. The policy definition of ‘movable’ or ‘relocatable’ housing does not

reflect the built reality or the way that residents understand their

(permanent) home. The resident owns rather than leases the unit so reselling is

the responsibility of the resident. This can be a long process, often the

resident feels financially locked into housing that is no longer appropriate. Physically,

the dwellings are raised off the ground – necessitating steps – and are small,

with minimum internal dimensions. Fringe suburban geography can limit walkability

as well as access to support services, to social participation with

the wider community, and to hospital and rehabilitation services after falls or

illness.

While MHEs for people over 55 years provide shareholder returns and elicit enthusiasm among some companies within the industry, they are not a supportive housing solution for ageing Australians.

While MHEs for people over 55 years provide shareholder returns and elicit enthusiasm among some companies within the industry, they are not a supportive housing solution for ageing Australians.

* * *

The consolidation that has shaped the industry direction since the early 2000s has narrowed rather than expanded the housing solutions being delivered. New retirement housing models are not innovations but are shaped by a ‘business as usual’ property formula to calculate development costs and risks against the local demand implicit in appreciating house prices. Retirement housing choices, in both demand and supply, reflect broader property market dynamics and interests. Segmented housing outcomes link the ability of ageing Australians to access care, and their capacity to continue to participate in their wider community, to wealth and geography.

There are four geographical dimensions to inadequate housing

choices for older people in Victoria.

First, there are limited opportunities to downsize in rural and regional areas.

Second, housing in well-serviced middle-ring areas is often homogenous and does

not include diverse (and smaller) options for downsizing. Third, housing can be

locally disconnected from community services. Fourth, there are few housing

choices for older people in private rental in all locations.

What

about solutions to address this last challenge, the seemingly intractable challenge of a

growing proportion of older people who do not own their home? The simple answer

is that this is an inevitable and foreseeable private market failure to

fill a known gap in the interconnected housing-and-ageing system. Home ownership

is entrenched in systems (pensions) of old age and public housing has been residualised over many years in Australia, limiting the capacity of both markets and policy to

respond to the increase in the proportion of older households who are housed

through the private rental market.

* * *

By developing retirement housing, health and care organisations engage in housing market dynamics, and property and house-building companies engage with care.

During the past decade, retirement housing operators have reshaped their involvement in aged care, developing less clear distinctions between the needs, choices and solutions of the third age and fourth ages. Retirement villages were not historically developed as places of care. Yet, their residents are ageing. Retirement housing solutions have undergone a rhetorical recoding, reflecting ‘ageing in place’ expectations and the growth of market-led home aged care services. Providers have understood the ageing of the population as demographically assured demand and, as their resident populations age, see an opportunity to augment their property development interests with the business of care. (Chapter 6.1 in the thesis discusses this in more depth).

* * *

The retirement housing sector

claims an economically important role in the business of downsizing and the business of looking after

older Australians. Yet, this housing option and its up-take (remaining around 6–7 per cent of people over 65 years) has not changed appreciably in 30 years. The industry is waiting for disruption; either at a tipping point of innovation

through engagement with care to serve an ageing baby boomer population, or ‘stuck’ as a minor housing option.

Will the ageing of the baby boomer

generation, understood as a demanding and discerning driver of market change, motivate

the industry to develop new forms of housing, and new ways of buying it and

using it to support a longer old age? And, will that innovation come from

the companies that currently constitute the industry?

Three avenues of possible future innovation:

1. Implementing more flexible ways of purchasing a lease.

Some companies are already exploring this with pre-paid or pay-as-you-go options. These release the model from the rigidity of its deferred payment structure and challenge assumptions about housing ownership in later life; however, they are essentially contractual changes for the same product and the same customer. Innovative ownership models (including through government investment) can widen the customer attraction, broadening from a focus on the wealthiest retirees to the full and part pensioners currently served only by the MHE market.

2. Targeting a service offer to meet the needs and desires of ageing residents living longer in their homes.

Again, many companies are already expanding their involvement in service and care. And, again, this has tended to target the more profitable parts of the service and care market, pursuing wealthy baby boomer customers seeking a ‘five-star’ lifestyle. Reconceptualising housing-and-care services together as essential infrastructures of ageing can help us think about the interdependencies between finance, geography, design, service, labour, welfare and markets.

Both these avenues require government investment to expand the market and deepen the integration of care. A third avenue:

3. Universal design and age-friendly cities

This is the obvious one - improving the design of new housing delivered in the general market, and improving urban environments that can support walkability, social connection, access to community services, and proximity to care providers. Housing and towns, once built, are fixed and long-lasting, so this change will be slow and gradual. We’d best do it now.

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis