Six weeks

Reflections on ageing: crisis, structure, imaginary, precarity, loneliness, fragility

1. crisis

It was only once I finished writing a

thesis about old age that I felt the overwhelming fear of my own ageing. A late

summer Tuesday night, I uploaded the finished pdf and clicked SUBMIT, stared

quietly at the laptop screen, drank a small glass of vodka, and had a relieved

little cry. It was a slight and anticlimactic moment concluding seven years of

a dragging and laborious PhD. Click SUBMIT and it vanishes for six weeks while unseen

examiners assess it. I had hoped those six weeks would be a languid late summer

celebration. Instead, once the manuscript had slipped into its electronic limbo, the weight of solemn academic papers and upsetting reports about old age turned

inwards on me.

For the first time I visualised my own old

age, as a graph at the point where the line starts to turn, and as a fleshy

ghost in the corner shadows of an Hieronymus Bosch painting. Skin hanging loose

from elbows, neck, brows, sparse white hair. Moving slowly and unsteadily,

vigilant of ‘the fall’, asking you to please speak up. Days stretch long and

lonely even as time becomes more finite. Talking too long and too close to the cashiers,

bar people, doctors, astrologers, masseurs, handymen. Then, repeating things, forgetting things, and slowly or abruptly becoming a tragic decision for someone else (who?)

to deal with, and then, even later, an unstill mind and collapsing body for women to

wash and roll and feed in 15-minute blocks of badly paid labour.

I was aware that this grotesque cliché of

deterioration is a commonplace mid-life reckoning, that the panic in my throat was

just the banal knowledge of time running out, but it was visceral during that

first week after submission. I would be celebrating my 40th birthday

in 9 months, and I knew what lay beyond it. I’d done the research. Ahead

of me stretched the second half of life, but everything was pre-determined, the

damage done, the foundations set.

2. structure

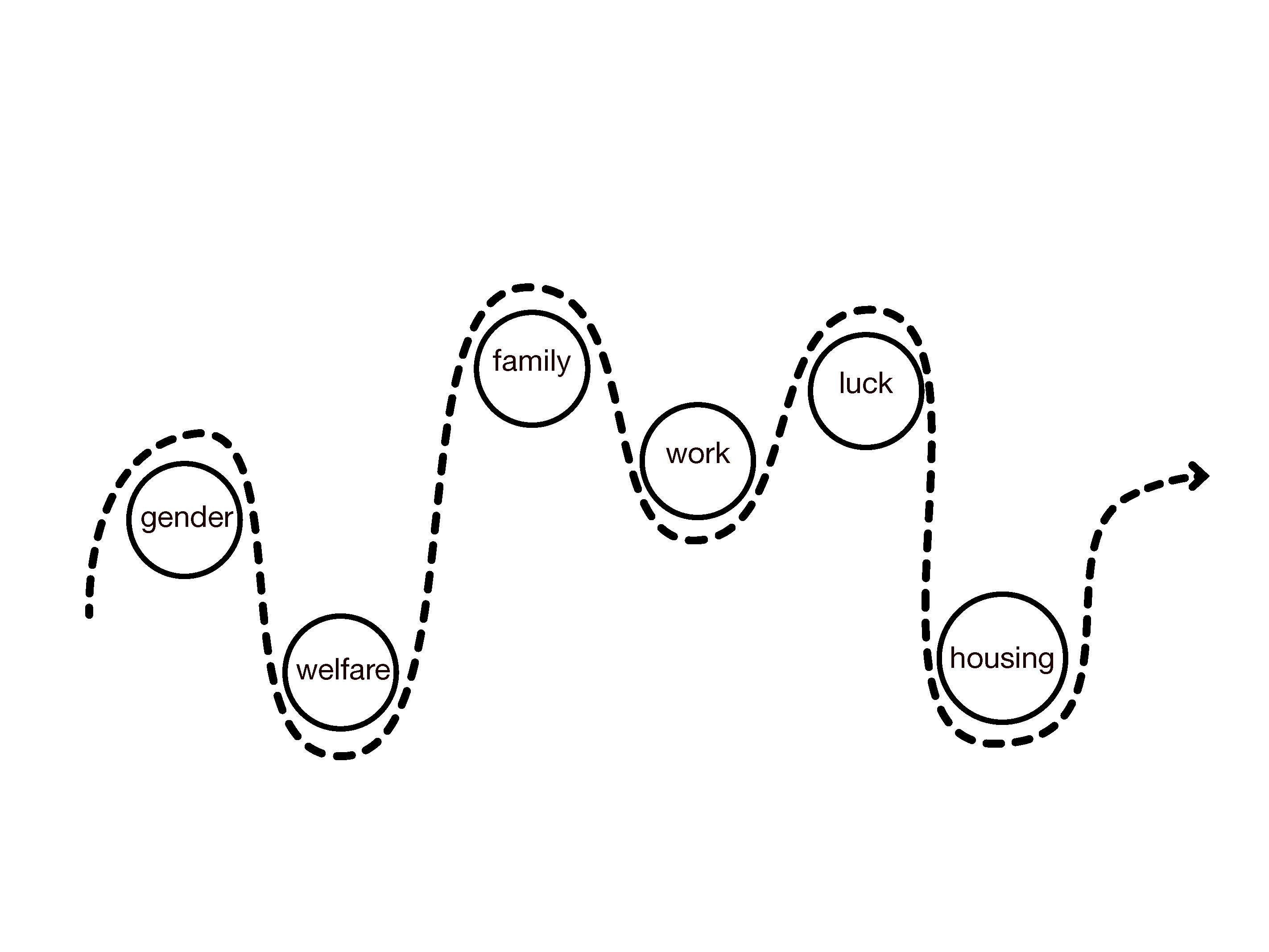

Foundations don’t work for life like they

do for buildings. The societal systems we are born into define narrow pathways

and choices and, even so, life bursts with sudden shifts, crises, luck. Old age

is an uneven social and economic structure, not a biology. It is shaped by

labour, welfare, retirement, taxation, migration, education, gender, family,

housing.

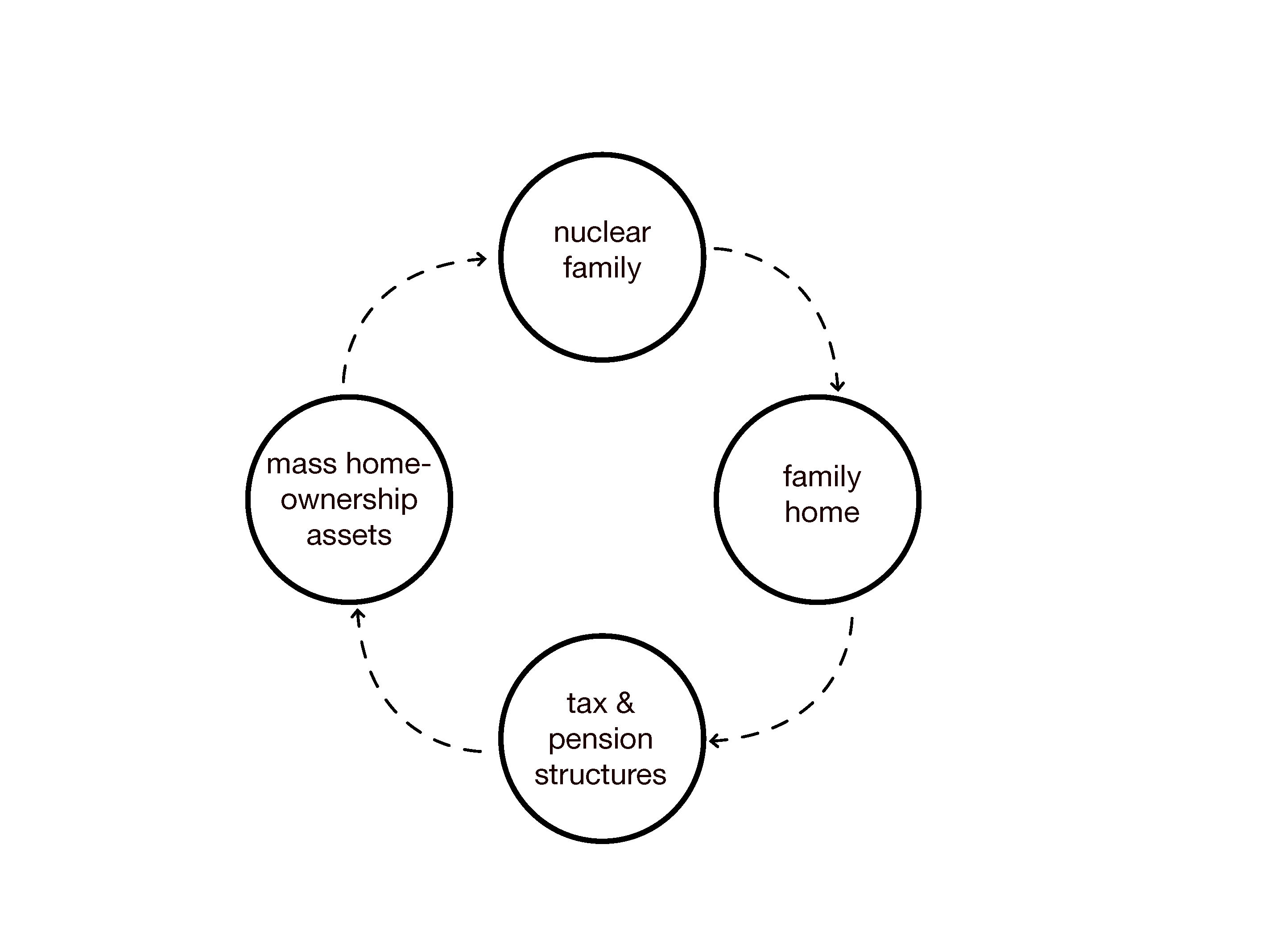

It is impossible to talk about old age without also talking about housing. Good, secure, affordable housing is essential for people’s physical and emotional wellbeing as they age. In industrialised liberal societies such as Australia, housing also takes on policy importance. The Australian solution of mass homeownership supports an affordable, secure old age because, by retirement, with outright ownership assumed, older-person households could live frugally on a state-provided pension. Rates of Australian home ownership (outright or with a mortgage) have remained at around 70 per cent since the 1960s.

It is impossible to talk about old age without also talking about housing. Good, secure, affordable housing is essential for people’s physical and emotional wellbeing as they age. In industrialised liberal societies such as Australia, housing also takes on policy importance. The Australian solution of mass homeownership supports an affordable, secure old age because, by retirement, with outright ownership assumed, older-person households could live frugally on a state-provided pension. Rates of Australian home ownership (outright or with a mortgage) have remained at around 70 per cent since the 1960s.

But the foundations are shaky. A crisis of housing affordability will limit

choices for younger generations as they reach retirement, as well as for

current retirees whose housing histories have not followed widely assumed

pathways. Older Australians who rent their homes in the private rental market,

disproportionally women, are more likely to live in poverty.

In the second week after submission, I had

a drink with my Ma in a city bar. She is 64, works in retail, has already withdrawn and spent

her scrapings of superannuation, and has lived in private rental since abuse and an

acrimonious divorce a decade ago. Hers is a common yet uniquely upsetting

story. That evening, she swept into the bar with an enormous sigh

and deposited two or three heavy bags on the marble counter, her stacked

bracelets of polished quartz, amazonite, tourmaline clacking on the cool

surface. The bags annoy me because she carries them around all day, shoulders

twisting with the weight, and then complains about her sore back.

“Oh my feet are so sore” she said, and I

recoiled with guilt.

She ordered a shiraz and announced; “I have some news.”

An advisor at her bank had told her that she could get a mortgage to buy a studio apartment.

“Now all I need is the deposit and then I’ll be paying less per month than I do now, and I’ll never have to have a house inspection again, and they won’t be able to kick me out. All I care about is getting my own place. If I have my own place I’m safe.”

Well, yes and no.

She ordered a shiraz and announced; “I have some news.”

An advisor at her bank had told her that she could get a mortgage to buy a studio apartment.

“Now all I need is the deposit and then I’ll be paying less per month than I do now, and I’ll never have to have a house inspection again, and they won’t be able to kick me out. All I care about is getting my own place. If I have my own place I’m safe.”

Well, yes and no.

3. imaginary

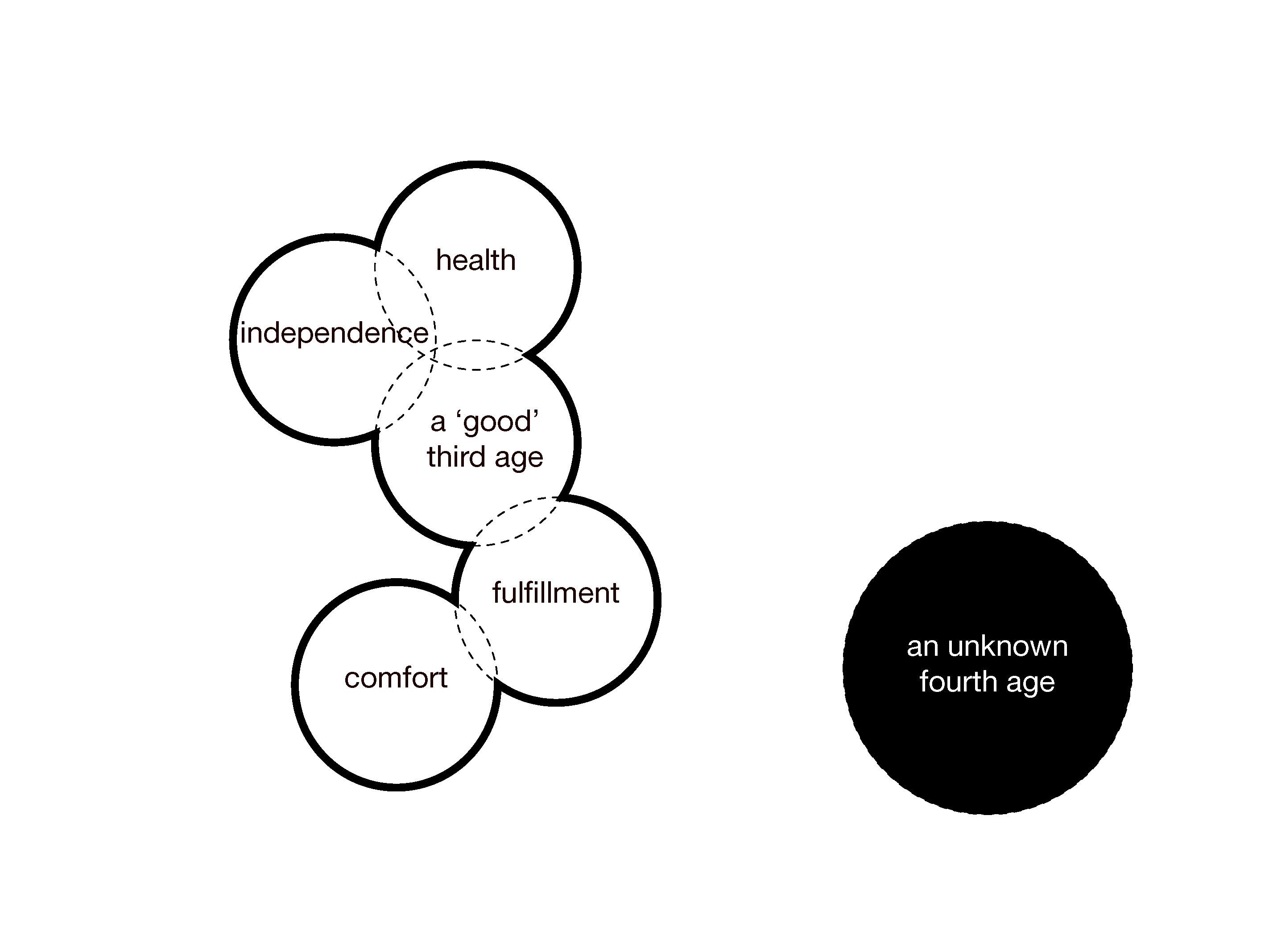

My mother’s story is a textbook case of the

wobbly foundations and bumpy pathways of the life course. The myth we tell is

that the baby boomer spends their Saturdays casually outbidding first-home buyers at property auctions in the inner suburbs. In aggregate, they constitute 15% of the population and

own 60% of Australia’s housing wealth. But in their real lives there is enormous

disparity. The wealthy independent baby boomer is a vivid imaginary. It

is a collective understanding of what constitutes a ‘good’ old age, wrought within

the enmeshed housing-and-ageing system and within narrow cultural norms. We

reproduce the baby boomer imaginary every day, in language, images, and in

products and services for older Australians.

The imaginary of the wealthy independent

baby boomer is an attractive vision of later life. I think it is what I

want, this good old age. Healthy, social, stable, active, sunshine, a

dog, green lawns. Everything fearful about old age is hidden, pushed deeper

into another phase of life. Being dependent is a deep fear in a society in

which autonomy is paramount. A celebrated third age of continued independence, extended by services and

supportive housing arrangements, aims to delay this fourth age dependence as long as

possible. Dependence becomes understood as a clinical and individualised need rather

than as an essential aspect that characterises social beings throughout life. The

cultural obsession with autonomy and choice obscures and marginalises other

experiences of old age. A focus on independence risks inadequately considering

the needs, desires and agency of the fourth age, and complex and diverse

transitions to dependence.

Through 2020 and early 2021 the COVID-19

pandemic and findings from major national public inquiries into aged care coalesced to highlight the stark realities of the fourth age. While Australia restricted international

travel and escaped high COVID-19 infection rates, 75 per cent of the 909 deaths that year were aged care residents and much of the spread of the virus in Melbourne was

transmitted by carers who worked casual shifts at a number of facilities. The

pandemic exposed the weaknesses of the aged care system’s dependence on

casualised and low-paid workforce. Further, months of isolation endured by aged

care residents (including those in facilities that did not suffer outbreaks)

drew attention to their mental and physical wellbeing and the quality of their

care.

The Australian aged-care system is a

political, economic and human disaster. The interim report of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and

Safety (2019) was titled simply ‘Neglect’. Some of the significant problems

in aged care are long waiting lists, opaque consumer information and choice,

providers on the verge of financial collapse, other providers delivering high

profits to shareholders, little transparency about a provider’s federal funding

and aged care spending, inadequate carer ratios (by this metric Australia ranks

very low internationally), low-paid and low-status jobs, a highly casualised

workforce, rising proportions of residents with dementia and systemic practices

of neglect. No one wants to go to an aged care facility, but the reasons people

need to be cared for are complex and ‘better housing’ is not going to solve

issues of human care.

4. precarity

In the fourth week after submission I left

work early on a Monday, and sat with my friend in a near empty cinema in

between rolling covid lockdowns to watch Nomadland. Frances McDormand

plays Fern; a 60-something woman left houseless by the

American industrial decline, living from her van, working seasonal shifts packing

Amazon orders and fast-food. She is grieving her deceased

husband, her previous life, and her past home on the edge of a town that emptied

when industry suddenly closed.

Fern herself is not simply a victim of post-industrial

social and economic upheaval, nor is she an agentic individual making free life choices.

She is both victim and agent, as we all are. Her decision to live, nomadically,

in her van is a choice within very narrow possibilities, and in the film she

crosses paths with many others who also make this decision and find joy and

pain in it.

After the film, my friend and I sat in dark mood lighting at a bar and had pizza and a bottle of wine and I thought, surely, if we pay off our mortgages, if we own our home, if the property market is to be trusted, if we are sensible, if we take responsibility for our financial resources, if we stay healthy, if we are lucky

enough to drop $26 on a pizza after a night at the cinema,that means we are safe from this precarious life.

Again, yes and no.

Again, yes and no.

5. loneliness

Loneliness has severe impacts on health,

especially in old age. Fern and her fellow nomads do not seem lonely. She’s a

nice person, people like her, many offer their homes for her to live in. After

submission I threw myself into spending time with my friends.

My friend has a vision of old age – it’s us in the future on recliners around a pool, reading books and imbibing food and drink and massages from the resort staff. Without highlighting the potential gaps in this dream (frailty, finance, family) I support the fundamentals of friendship and fun. But the greatest flaw in logic is planning for succession, because what if the pool-side recliners are one day filled with grief, or worse with a newly arrived stranger who watches me suspiciously for signs of decline.

My friend has a vision of old age – it’s us in the future on recliners around a pool, reading books and imbibing food and drink and massages from the resort staff. Without highlighting the potential gaps in this dream (frailty, finance, family) I support the fundamentals of friendship and fun. But the greatest flaw in logic is planning for succession, because what if the pool-side recliners are one day filled with grief, or worse with a newly arrived stranger who watches me suspiciously for signs of decline.

One quarter of Australian

women don’t have children and sometimes I feel like I know all of them, and then

occasionally they announce they are pregnant. We need to

invest in intergenerational connections in addition to the reproduction at centre of the nuclear family... which is the foundation of the family home... which allows a low pension... and which in turn requires homeownership as an

essential pillar of a ‘good’ old age. It will be hard to break the circle.

6. fragility

In the sixth week after submission four

friends and I went camping. We each strapped a tent, mat and sleeping bag onto

our bicycles and met at the train station, clustered under the departure boards

with our bright outdoor gear like an amateur Everest base camp. We took a train

an hour west to where the suburbs become country towns and we rode into the

bush. It was summer’s last gasp. Four-wheel-drives passing us on the dirt roads

threw up clouds of dust that hung like mist in the hot air. We curled slowly up

hills and then down into the thick forest trail.

The world closed in quickly. Five figures on a thin thread of a track, twisting through thick fern

undergrowth. Tall gums filtered the heat. The sounds of the bush ricocheted

around this verdant vessel; raucous bird-calls, rustling leaves, a creek stirring

in the gully below. The track carved narrow and deep into the coiling

terrain so that in places we had to paddle our bikes like boats, feet pushing

along the banks.

We moved like this for three hours barely

covering 10km, then at the pit of the valley we took our shoes off, crossed the

shallow summer river, and set up camp while the orange sun still hit the

branches above. I thought later in a panic: There could have been snakes, we

could have fallen, we could have been injured, our bikes could have broken, we

could have died. We could have died in this pocket of relative wilderness,

barely one hour from central Melbourne.

You don’t have to go far from the city to feel that you are a speck, an insignificant moment within the land’s seasonal cycles and geological layers.

You don’t have to go far from the city to feel that you are a speck, an insignificant moment within the land’s seasonal cycles and geological layers.

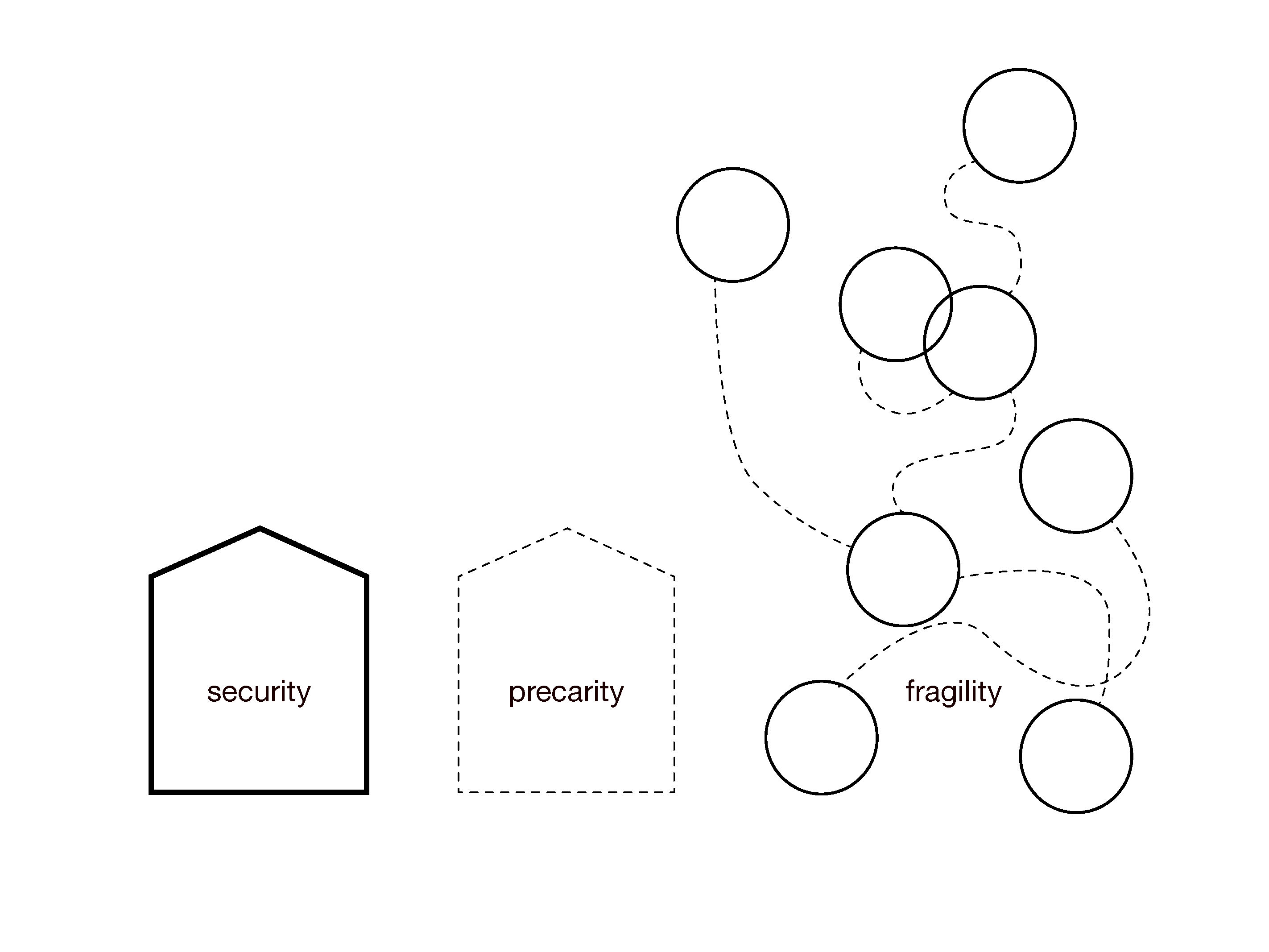

Security is the wrong aim in this world. Our brief lives

crinkle on axes outside of our control. Embracing fragility belies our human,

social and policy responses to fear and it contradicts the life-long pursuit of

stability that has unleashed a chain of property accumulation and intergenerational

inheritance. We need to acknowledge that this conception of security is the

wrong philosophical aim to safeguarding our old age. The wafer-thin boundary that protects (natural) fragility from (dangerous) precarity is not constructed of individual

security but of social networks that hold us through change and crisis. That is what we

need to invest in.

In the end it took more than six weeks for

my thesis to come back to me, passed. It was by then early winter, my crisis had dulled,

urgency for change abated, I no longer cared as deeply about my own old age, the delusions were that strong.

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis

I research and write about social and urban issues and their theory, policy, and industry intersections.

Alongside my research I work in urban renewal, helping government shape the strategies and outcomes of long-term large-scale precinct development to achieve economic, social and sustainability goals.

In both my research and practice I transform complex projects and problems into clear ideas and directions.

Contact: kirsten@kirstenbevin.com

Download CV

Publications:

James, A., Crowe, A., Tually, S., et al. (2022) Housing aspirations for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 390, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., et al. (2022) Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians, AHURI Final Report No. 378, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: industry engagement in older persons housing, PhD Thesis, RMIT University.

Bevin, K. (2018). ‘Shaping the Housing Grey Zone: An Australian Retirement Villages Case Study’, Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215-229.

Bevin, K. (2016). ‘Diversity and disparity: Retirement housing in age-friendly cities’, in Future Housing: Global Cities and Regional Problems. Melbourne: Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, pp. 93-99.

Building buffers: Talk for the DADo Film Society (Sept ‘24)

Making housing shaping old age: Summary of PhD thesis

The story of retirement housing in Victoria: Case study within the thesis